Serotonin feels great so we want it all the time, but it’s not designed to be on all the time. Our brain releases short spurts in appropriate moments, and it’s quickly metabolized. So if you’re not always feeling it, that’s normal.

The ups and downs of serotonin are easier to accept when you understand its natural job. I’ll explain that here, and you can get the full story in my books on this subject, which are all excerpted at the Inner Mammal Institute.

The job of serotonin is to motivate self-assertion.

It turns on when you see yourself in a position of strength. Serotonin is not aggression but a sense of calm confidence. You may not like the idea that a position of strength is what makes us feel good, so let’s start with the animal perspective.

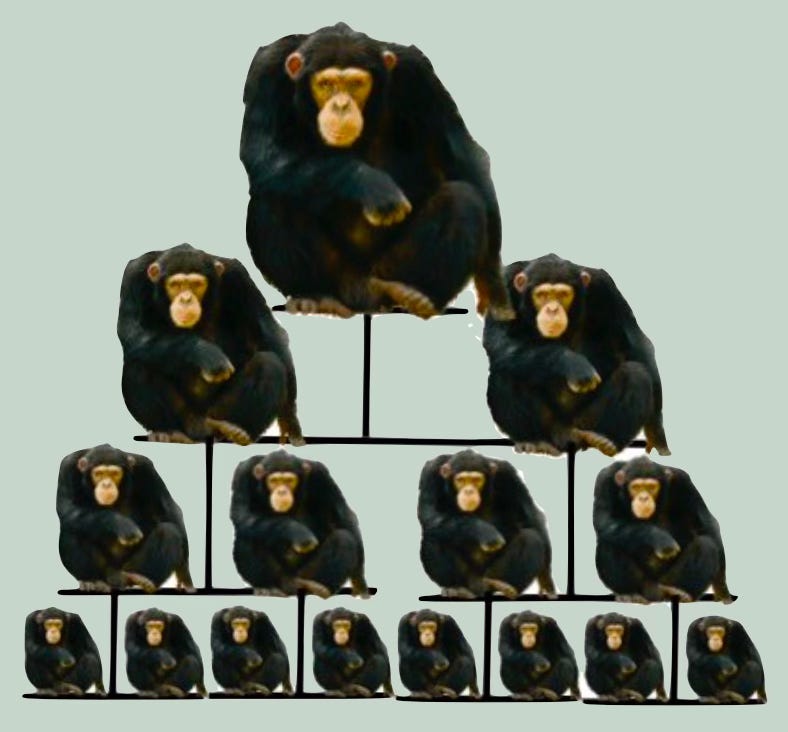

A monkey in nature is always looking for food, but if it reaches for food near a stronger monkey, it is likely to get bitten or smacked. Pain triggers cortisol, and that wires the monkey to fear reaching out near stronger individuals. But it’s still hungry, so it looks for an opportunity to be in the position of strength. Serotonin is released when the mammal brain sees that it’s in the one-up position. It’s the brain’s signal that it’s safe to assert. Serotonin relaxes your body when you decide that you are strong enough to meet your survival needs in a world full of rivals.

Cortisol does the opposite. It’s the brain’s signal that you need to pull back to protect yourself. It triggers a full-body sense of alarm that prepares you to face a threat. The mammal brain is always looking for ways to spark serotonin and relieve cortisol.

Whenever two monkeys cross paths, one of them makes a dominance gesture and one makes a submission gesture. Each brain quickly checks out the other and makes a choice. When a monkey sees that it has the advantage, it raises its head and shoulders and stares directly into the eyes of the other. Now the second monkey must decide. It could make a submission gesture by lowering its head and eyes, which says “you don’t have to hurt me because I will yield on any resource that comes along.” Or it could make a dominance gesture, which says “I dare you to fight me.” Now, the first monkey either submits or does battle. Monkeys rarely fight because they are good at predicting who would win. But they always compare themselves to others and clarify their status with the dominance-submission ritual.

Researchers have found this behavior in all mammals, from dogs to cows to gorillas. The research began with a 1922 PhD dissertation on the pecking order of chickens. Schjelderup-Ebbe had grown up with chickens and noticed that they always ate in a specific order. The biologist saw that they were attacked if they went out of turn, but otherwise lived in peace unless the flock gained or lost a member. Then, each chicken fought each other, and a new order was established. He coined the term “pecking order,” and inspired others to research this natural behavior.

The stakes are higher when mating opportunity is the resource at play. A monkey who never asserts will never reproduce, and its genes will be wiped off the face of the earth. But a monkey who asserts against a stronger rival may get killed before it passes on its genes. Natural selection built a brain that makes good decisions about when to assert and when to hold back.

We have inherited our brains from individuals who did what it took to keep their genes alive. We’ve inherited a brain that makes social comparisons and reacts with neuro- chemicals. Our brain creates life-or-death feelings about how it stacks up against others. You may not want to think this way, and you may insist that you don’t. But your brain goes there without conscious intent because it likes the serotonin. You benefit from understanding this fact, even if you don’t like it.

You deprive yourself of serotonin if you refuse to feel proud of yourself. You fill your life with cortisol if you see yourself as the little monkey who never gets the banana. I’m not saying you should dominate others to spark serotonin. I’m saying that you will seek moments of social dominance, and you will feel endangered when that quest is disappointed. So you need to understand the way your thoughts control these emotions. Otherwise, you will feel like a powerless victim of other people’s dominance-seeking.

I found great peace when I learned the serotonin facts of life. I stopped feeling judged because I knew how my own brain was doing the the judging. I stopped feeling broken because I realized that every brain makes social comparisons and reacts with strong chemicals. I stopped defaulting to old responses because I saw that they were my internal creation, not external reality.

I wondered why no one told me the facts about serotonin in my decades of studying psychology. You may be wondering where my facts come from, and how they can be true if they’re never mentioned in the mental health world. So let’s answer those questions.

My knowledge of serotonin comes from research done at UCLA Medical School and the US National Institute of Mental Health, as reported in the New York Times in 1983. Links are on the serotonin page of my website, InnerMammalInstitute.org/serotonin. This research was widely discussed in the fields of biology and psychology in the late 1900s, but it suddenly disappeared. Here are three reasons why it disappeared, starting with the least well known.

At the end of the twentieth century, animal rights groups made violent attacks on monkey researchers. To protect themselves, universities stopped the research and withdrew findings that were already published. The internet began around this time, so the truth was left out of the burgeoning new websites. Only dusty paper books still report it.

The second reason why the serotonin facts disappeared is that they violate the belief system of the academic world. Academics believe that nature is good and “our society” is the cause of everything bad. You probably agree with this Rousseauian paradigm because our education system is rooted in it. It’s so well-entrenched that we think it’s a fact rather than a belief. We’re taught that animals are good, children are good, and hunter-gatherers were good, and when you see bad behavior among animals, children, and hunter-gatherers, you learn to blame it on “our society.”

You are told that science proves this, but you don’t learn the way science is designed to support the belief system. Academics are celebrated and promoted when they find evidence that fits the Rousseauian paradigm, and they are ignored or attacked when they violate the paradigm. Graduate students can easily figure out this reward structure. If they present animals as cooperative and altruistic, they will get recognition. If they document the conflict in nature, they will disappear. So we end up with lots of “studies” on the kindness of animals and rarely hear studies on the social rivalry among animals.

For most of human history, people could see the conflict between animals for themselves. They would have laughed at you if you said that animals are altruistic. But as people moved to cities, they could not observe animals for themselves, so Rousseau’s theory was accepted as fact.

The third reason that the serotonin facts disappeared is something you may have guessed: pharmaceutical companies sold a different view of serotonin. They paid doctors to embrace the view that serotonin-boosting medication is the way to be happy. This view was sold so thoroughly that a doctor can lose their license if they question it. So licensed members of the healthcare profession will only tell you that a chemical “imbalance” is the problem and pills are the solution. A more complete explanation is in my book, Why You’re Unhappy: Biology vs Politics.

You may insist that you are too nice to get pleasure from being in the one-up position. Here’s a simple way to understand the feeling. Imagine that you are playing poker and you draw the card you need to win. Suddenly, a great feeling surges. That’s because winning feels good, as much as you hate to admit it. If you decided that it’s wrong to win, you would not play cards because there would be no enjoyment. Serotonin is the brain’s reward for finding a way to prevail.

I want to clarify again that I’m not saying you should strive to dominate others. That would just lead to fights. The challenge of life is to feel pride without getting into messy conflicts. In past generations, people carried swords and pulled them out when they thought their social dominance was challenged. Today, we play video games. We cook gourmet meals. We race on exercise bikes. Anything that gives you the one-up position in your mind gives your inner mammal the peace of serotonin. But the chemical is quickly reabsorbed, which is why we look for one-up moments again and again, despite our best intentions.

You can see the urge for social dominance in other people, especially those you don’t like. But in yourself, it’s hard to admit to the social comparison that drives your emotions. We are trained to condemn this urge, so we mask it with fancy theories. Let’s see how our brain creates the urge for serotonin without our conscious awareness.

We humans have two brains. The pink fluffy brain you see in pictures is the cortex that’s unique to humans, but inside that we have the limbic system common to all mammals. Your cortex controls language, but your mammalian brain controls the chemicals that make you feel good and bad. Animal can’t talk, so your mammal brain can’t tell you in words why it turns on a chemical. That’s why our emotions are so hard to understand.

The talking part of your brain keeps trying to explain your emotions, but it lacks insider information. So we explain our emotions in the ways we hear from others. But they don’t know the facts about their limbic system, so we end up with false beliefs about our emotions. The most common belief is “You made me feel that way.”

To get the real inside story, let’s go back to monkeys. Young monkeys spend a lot of their time wrestling. Humans call this “play,” but it is serious business because it wires their brains to feel their own strength. When they’re overpowered by a bigger monkey, cortisol warns them to back off. When they have the advantage, serotonin makes them feel safe.

Neuro-chemicals act like paving on our neural pathways. Neurons connect when these chemicals flow, which wires us to repeat behaviors that spark good feelings and avoid behaviors that spark bad feelings. The biggest pathways in the brain get built in youth because that’s when we have an extra highway-building material called myelin.

You built myelinated pathway in the serotonin moments of your youth. That’s why you seek serotonin in particular ways today. If you scored points in sports when you were young, your brain got wired to turn it on in the context of sports. If you scored points in school when you were young, your brain got wired to turn on the serotonin in a similar context. If you scored points at parties when you were young, your brain got wired for positive expectations about parties.

It works in the opposite direction too. If you failed to score points in sports as child, you built cortisol pathways that turn on bad feelings about sports later on. If you failed to score points in school as a child, you wired in bad feelings of school-related situations. If you failed to score at parties, you bring those cortisol pathways to parties today. Of course it’s more complicated because we all have a wide range of experiences. But the biggest neurochemical surges of your youth built the biggest pathways in your brain.

We don’t remember the experience when we use the pathway. We just flow into old pathways because the electricity in the brain flows like water in a storm, finding the paths of least resistance. Your old pathways are so efficient that you flow there without realizing that you have a choice. We are capable of redirecting the flow, but it’s like trying to divert a river into a soda straw. It takes 100% of your attention. It gets easier if you repeat a new choice because a new pathway grows, but it’s hard to do the repetitions while you’re running on old paths. All of my books and courses explain how to do this.

We are born with billions of neurons but very few connections between them. Connections build from experience, so we all face the adult world with a neural network built in youth. You may jump to the conclusion that other people had better experiences and got better pathways. But consider this. Most historical figures had terrible childhoods. They faced real threats so they built skills and learned to trust their own skills. By contrast, a very protected child who never cuts their own meat will not wire in the pleasure of trusting in their own strength.

You may think some people float through life on an effortless cloud of serotonin, while you are cruelly deprived. But let’s imagine a jet-set lawyer charging $1,000 an hour to celebrity clients. You may think they coast on endless one-up feelings, but in fact they spend their lives submitting to clients, bowing to judges, and fighting off attacks from other lawyers.

Serotonin doesn’t last because the brain habituates to the rewards it already has. For example, when you walk into a flower shop or a chocolate shop, the smell triggers the joy of dopamine at first, but your brain stops noticing the good smell in a short time. It’s the same with serotonin. You think you’ll be happy forever if you get a particular promotion or award or romantic partner, but your brain soon takes it for granted and looks for a new one-up moment.

If you hit a home run, you enjoy it for a short time, and then you’d start worrying about the next hit. If you were on the top ten billionaires list, you would worry about up-and-coming billionaires knocking you off the list. Losing rewards feels bad even if having them doesn’t make you happy. You don’t intend to think this way, but it’s useful to know that it’s natural.

When a toddler and a dog are in the same room, the toddler wants the toy that the dog has and the dog wants the toy the toddler has. Each mammal looks for ways to assert itself because the brain rewards you with serotonin when you prevail.

Now imagine two toddlers in a room full of toys. Each toddler tries to grab the other kid’s toy. Adults often intervene and teach a child that it’s wrong to grab or bite to get what you want. But no one teaches you the reason why you want that toy so much. Then puberty comes, and you want what others have even more.

Our mammal brain creates a sense of urgency about whatever sparks our chemicals, while our verbal brain looks for good reasons to justify these impulses. Your talking brain finds ways to make you look good while you seek what makes your mammal brain happy. When you talk to yourself, it’s all in your cortex, but your mammal brain controls that chemicals that make you happy or sad. Your inner voice may seem like the showrunner but it’s just the narrator.

It’s hard to accept the truth about your inner mammal when you’re trained to see animals as loving and kind. I understood the truth when I watched nature videos that showed how monkeys stuff their cheeks with food and run to hide before swallowing. The cheek pouches evolved because stronger monkeys literally grab food from the mouths of weaker monkeys. Animals learn to deal with social rivalry in youth. Monkeys do not feed their children, except for mothers milk. Little monkeys learn to feed themselves with mirror neurons that activate when their mother grabs food. Big monkeys tolerate the grabbing of little monkeys as long as the little ones have the “juvenile marking” of their species, like a white tuft of fur on their head. Once those markings fade, at around three months of age, a little monkey has to navigate the social world to avoid starving.

The warm-and-fuzzy view of animals is deeply entrenched in the media and academia, and that makes it hard to understand your chemical ups and downs. The romanticized view of nature is seen as the mark of an educated person, so you risk being condemned as a unethical or stupid if you acknowledge the conflict in nature.

What’s a big-brained mammal to do?

It helps to know that we all face the same dilemma. We’ve all inherited the operating system that kept our ancestors alive. This contraption is hard to manage so we have to build the skill throughout life. You don’t build the skill when you’re told that you’re not responsible for your emotions. You don’t build it when it’s taboo to acknowledge your natural impulses. Today’s culture discourages people from finding their power over their brain. It encourages you to expect good feelings all the time and to blame society and the healthcare system if you don’t have it.

Humans have struggled to manage the urge for social dominance since our species began. In the past, violence was so common that people rarely left their village in a lifetime. Today, most people learn better ways to spark the one-up feeling that we naturally long for. You may not like other people’s strategies. You may sneer at people who feel superior about their looks or their money or their social media. So it’s important to notice that moral superiority is just another way of sparking serotonin. You can decide that you are morally superior to people with better looks or possessions or social-media numbers. This gives you the one-up position without getting off the couch. But this strategy leaves you bitter a lot. And it doesn’t the build confidence in your own skills that your inner mammal needs to feel safe. It’s hard to stop this moral-superiority game because it’s a big highway in your brain. But you can build a new highway when you know how your brain works.

All of my books help you do this. Two of them are exclusively on this topic:

Status Games: Why We Play and How to Stop and I, Mammal: How to Make Peace With the Animal Urge for Social Power.

Serotonin will always be a struggle because we are born helpless and vulnerable. To a baby, getting attention is a matter of life and death, so we wire in life-or-death feelings about getting attention. But in adulthood, you see a world with eight billion other people who want to be special just as much as you do. So we all have to manage the frustration of not being special. When you know the natural roots of this feeling, it’s easier to accept yourself and everyone around you.

You can make peace with your inner mammal regardless of what others do. You can build skills that you’re proud of, and focus your attention on that. You will still notice better skills in others sometimes, and react with one-down feelings. But with practice, you can re-direct your focus toward your strength.

To help you get real about your serotonin impulse, I have collected the words we use to describe it. Here is my list: pride, self-confidence, ego, ambition, status, glory, dominance, honor, dignity, self-worth, prestige, prominence, grandiosity, power, exclusivity, social importance, recognition, acclaim, approval, self-aggrandizement, getting respect, influential, arrogance, assertiveness, manipulativeness, competitiveness, one-upmanship, being special, influential, or a winner, feeling superior, having class, saving face.

I hope this podcast has been helpful, and I hope you will pass it on to others, to help them make peace with their inner mammal.